|

| Lithograph of Norrkӧping, Sweden in 1876. (Wikipedia) |

Left: Information from Sander’s certificate shows he was born in ӧstergötland, Skärkind, Sverige (Sweden) on December 12, 1868. He was a farmer (dräng) who, in 1888, left Matthew Church Parish Norrköping in ӧstergötland for North America. (Sweden, Emigrants Registered in Church Books, 1783-1991. Ancestry.com)

Near the beginning of May 1888, Sander

and his family went to the railway station in Norrköping where he would

begin his long journey to America. Emotions were running high as

he boarded the train to begin the four-hour trip across Sweden to the

western port city of Göteborg (Gothenburg). He wondered when, and if, he would see his family again.

|

| Approximate train route from Norrköping to Göteborg, Sweden, about 200 miles apart. Railroads had to circumvent the many lakes that cover southern Sweden. (Google Maps) |

– Göteborg: PORT OF DEPARTURE FROM SWEDEN –

In Göteborg, Sander presented his paperwork to officials and had the routine physical exam to make sure he was healthy. An emigration agent from the shipping line confirmed his third-class ticket. In 1888, passage for just the Liverpool/New York leg was about £4 ($640 in 2022). It was more economical for travelers to purchase a travel pack, also known as an emigrant contract (utvandrare-kontrakt), rather than individual tickets for each leg. [See a 1904 contract here.]

The contract included meals, accommodations, passage from Göteborg to Hull and Liverpool to New York, a rail ticket from Hull to Liverpool, and another from New York to the emigrant’s final destination in the United States. It also included meals and lodging at all stops since there could be delays up to a week or more due to railroad and ship arrival/departure schedules.

Another benefit of the contract was that emigration agents from the shipping line were at every port to escort, translate, and otherwise aid emigrants. Sander and his fellow travelers were directed to purchase a mess kit (jug, cup, metal bowls, utensils), a mattress and blanket, along with some food to supplement meals as they traveled. Those who didn't regretted their decision later.

This scene is similar to what Sander would have observed as the crew of his ship prepared for its voyage to the city of Hull on the eastern coast of England.

Right: Farewell to home – emigrants bound for England and America – on steamer at Göteborg, Sweden circa 1905. (Library of Congress)

|

The steamer S.S. Orlando circa 1880. (Augustana College, Swenson Center Image Gallery) |

|

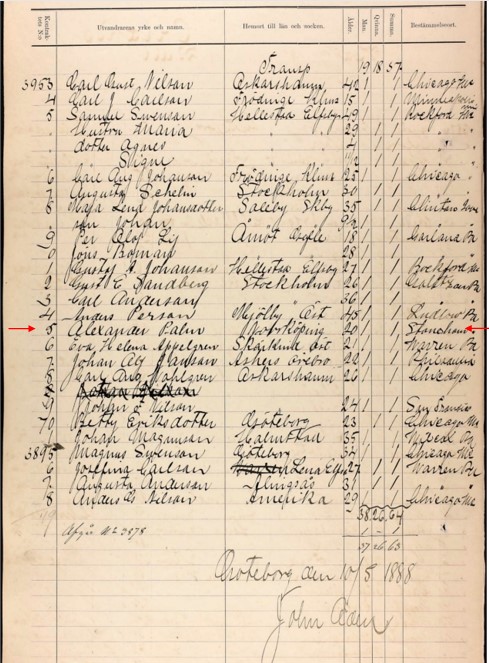

| Orlando’s list of emigrants departing Göteborg, Sweden for Hull, England on 10 May 1888. Alexander Palm is passenger #3965. He is from Norrköping, age 20, male, and has one piece of baggage. His U.S. destination is Stoneham [Pennsylvania]. (Ancestry.com) |

By the time travelers arrived in Hull, most were hungry and exhausted both from lack of sleep and seasickness after the rough passage across the North Sea. Those who brought extra provisions were glad they did.

_wikimediacommons.jpg) |

|

Shipping off Victoria Pier, Hull by Thomas Somerscales. Oil on canvas, 1894. "A splendid view of the Victoria Pier on a choppy day with magnificent representations of Humber keels with their large square sails, the classic local sailing barges, a Hull-New Holland paddle steamer at the pier and a steamer beyond which is probably coming out of the Humber dock basin." (Wikimedia Commons) |

– THE HULL-LIVERPOOL RAILWAY –

_England_early_1900s_or_before_postcard_lighter.jpg) |

| Paragon Street Station. Hull. Circa early 1900s. Station Hotel, with original porte-cochère entrance. (Wikimedia Commons) |

|

Railway Junctions in Hull by Railroad Clearing House, 1914. (Wikimedia Commons) Paragon Street Station is highlighted. |

|

[A station throat is the often constricted area at the end of a railway station where running lines divide into platform tracks.]

|

|

My

dotted line indicates Sander’s approximate route from Norrkӧping

to Liverpool. (Google Maps)

|

Sander had to be overwhelmed by Liverpool. In 1888, the city’s population was approaching 620,000, over seven times that of Norrkӧping. (Vision of Britain) Emigrants could spend over a week in the city before their ship actually sailed, since tides, scheduled arrival/departure times, and loading/unloading baggage and passengers all influenced actual departure times. Sander was probably in the city for only a day, however. As always, emigration agents from the National Line escorted Sander and his fellow travelers from the train station to hotels or boarding/emigrant houses.

– THE PORT OF LIVERPOOL –

|

|

The Port of

Liverpool and the River Mersey. Note the docks (in red) lining the right bank

of the river. (Google Maps)

|

When the day arrived to board his ship, National Line’s S.S. Egypt, Sander was thrust into the bedlam of the Port of Liverpool, an enclosed dock system stretching over seven miles along the east and west banks of River Mersey. (Liverpool) The Czech writer, playwright, and critic, Karel Čapek, described Liverpool in his 1924 book, Letters from England, after visiting the city the previous year:

... Liverpool is the biggest port ... there was something to see from Dingle up to Bootle, and as far again as Birkenhead on the other side. Yellow water, bellowing steam ferries, white trans-atlantic liners, towers, cranes, stevedores, skiffs, shipyards, trains, smoke, chaos, hooting, ringing, hammering, puffing, the ruptured bellies of the ships, the stench of horses, the sweat, urine, and waste from all the continents of the world ... And if I heaped up words for another half an hour, I wouldn't achieve the full number, confusion and expanse which is called Liverpool.

Shipping line agents led the emigrants through the crowds to the staging area dock. While Sander and the other passengers waited, ship tenders transported small groups to Egypt, lying some distance down river. Sander had to feel some sense of relief knowing that, even though this would be the longest part of his journey, he would soon be in America.

| |||

|

Postcard view north over George's Dock, 1897. The Liverpool Overhead Railway runs across the centre of the image, with St Nicholas church to the rear. (Wikimedia Commons) |

_wikimediadotorg.jpg) |

|

Landing Stage, Liverpool, circa

1903. (Wikimedia Commons)

|

Sander's ship, S.S. Egypt, was a steamer built in 1871. It sported two funnels and four masts. It was built for speed, safety, and a larger capacity for both cargo and

passengers. (Norway Heritage)

|

| "The magnificent steamships Egypt and Spain" by Charles R. Parsons. 1879. Lithograph by Currier & Ives. The steamers, Egypt and Spain, off Sandy Hook outside the Port of New York. S.S. Egypt is under sail and steam and flying a Red Ensign. (Wikimedia Commons) |

Egypt's first-class passengers were housed in the 120 berths located around its grand saloon, such as those on the steamship Drew, shown below. Other saloons included an elegantly furnished dining room, smoking room for the gentlemen, a ladies’ boudoir, and a library. The saloons, state-rooms, and officers' rooms were heated by steam-pipes.

|

|

The grand

saloon on the steamer, Drew, which ran on the Hudson River between New

York and Albany, circa 1878. (Library of Congress)

|

Sander was traveling third-class in steerage and, according to Egypt’s manifest, he was assigned to forward steerage located on one of the ship’s lowest decks. The area had open-berth compartments arranged around the perimeter of the deck; an open space in the center provided a place where passengers could gather or tables could be set up for meals. While the accommodations were better than those of Orlando, they were still far from ideal.

Egypt’s steerage, located among the machinery spaces of the ship, held 1410 passengers when fully booked, allowing each passenger approximately fourteen square feet of space. Imagine all those passengers sharing the minimal bathing and toilet facilities. Even though light and proper ventilation had improved a great deal since the early days of ocean travel, it took only a day or two before the foul air and filth from human waste and vomit made it difficult to breathe. (Norway Heritage)

In the days before steamships it took a month or more to

cross the Atlantic, making steerage the perfect breeding ground for diseases such

as cholera and typhus. Adding to the problem, crews usually put off the

unpleasant task of cleaning the facilities until the last day of the voyage

when everything on board had to be in tiptop shape for the inspection at the Port

of New York. By the time Sander made the voyage, it could be made in seven

or eight days, reducing the risk of disease to some degree.

During fair weather, people spent as much time as possible on the open deck designated for steerage passengers. First-class passengers had their own deck. When the ship encountered inclement weather, steerage passengers were forced to stay below and endure the horrific conditions – very little light and poor (or no) air circulation – while they were buffeted by rough seas.

Left: Emigrants

on the crowded lower deck of a ship in mid-ocean. Circa 1890. (Library of Congress)

In addition to the cramped conditions, steerage passengers were subjected to other indignities. Generally, ships’ crews treated those passengers with disdain, displaying rude behavior and sometimes getting physical by pushing or shoving. The rations steerage passengers paid for were supposed to be of good quality and sufficient for the journey, but portions were usually meager, poorly prepared, and sometimes spoiled; drinking water was frequently dirty. [See Immigrant's Voyage in Steerage – 1888, the same year Sander made his voyage.]

Egypt completed the voyage from Liverpool, England in about a week, arriving at the New York Bay staging area on May 21, 1888.

The dotted line through New York Bay indicates the main ship channel.

-

In 1888, the first structure

visible to emigrants as their ships approached New York was the Elephant Colossus (1) located on Coney

Island at West Brighton Beach.

- Fort Hamilton (2), is an historic Revolutionary War battery, originally known as the Narrows Fort.

- The Statue of Liberty (3) is eight

miles north of the western tip of Coney Island.

- It is another mile to Castle

Garden (4) on the southern tip of Manhattan Island. This is where emigrants were processed before being admitted to the United States. The facility on Ellis Island didn't open until 1892.

- Sander took a train from the Pennsylvania Railroad Station (5) in Jersey City to Stoneham.

|

PRR (1893) Railroad Lines New York Harbour. Cropped image. (Wikimedia Commons) |

|

|

The Elephantine Colossus, circa 1895.

Urban Archive, Center

for Brooklyn History.

|

|

| Saturday half holiday, bound for Coney Island, U.S.A., 1892. Stereograph card. (LOC) |

Next, Sander's ship passed Fort Hamilton (2) on the east side of the Narrows. This historic battery is where, on July 4, 1776, American patriots fired on one of the British man-of-war ships in the massive British fleet that was assembling in the Narrows. While the shot caused some damage, it did little to prevent General William Howe's August invasion of Long Island. (Historical Markers)

|

| Forts Hamilton and Lafayette, The Narrows, New York, From Staten Island by John Perry Newell (1832-1909) (Doyle) |

Left: New York - Welcome to the land of freedom - An ocean steamer passing the Statue of Liberty: Scene on the steerage deck. (Library of Congress)

The Statue of Liberty, a copper statue that stands just over 151 feet high, was a gift to the United States from the people of France. It was erected in New York Bay in October 1886. The combined height of the statue and its pedestal from the ground to the tip of the torch is 305 feet, making it easily visible as S.S. Egypt made its way north through New York Bay. (Wikipedia)

|

|

The

city of New York. 1886. Currier

& Ives. Castle Garden is the round building at

the lower left. (Library of Congress)

|

Castle Garden was an imposing structure that started its life as a fort – the Southwest Battery – in 1811. When New York City took possession of the fort in 1823, it was renamed Castle Garden and used as an opera house and theater. Beginning in 1855, the State of New York used the structure as a processing facility for emigrants arriving in New York City by sea. In August 1892, processing started in the newly constructed facilities at Ellis Island, operated by the federal government.

The first night in New York Sander and Egypt's other passengers stayed on board ship in the staging area. The next morning, baggage and other items aboard ship were inspected. Then emigrants were given brass tags in exchange for their baggage as it was loaded onto barges. After passengers were transported to Castle Garden on ship tenders, they used the tags to claim their baggage.

|

|

New York Bay, Castle Garden [Castle

Clinton], and Statue of Liberty. (LOC)

|

Once inside Castle Garden, people were interviewed by immigration agents, examined by doctors again, and directed to the rotunda where they could purchase train tickets, if needed, and exchange currency.

Left: Immigrants landing at Castle Garden. Drawn by A.B. Shults in 1880. Published May 29, 1880 in "Harper's Weekly." (LOC)

Left: Interior of Castle Garden. The rotunda filled with immigrants. (Library of Congress)

|

|

In

the Land of Promise, Castle Garden, painted in 1884 by Charles Frederic

Ulrich, is a depiction of the emigrant landing depot in Manhattan. [National Gallery of Art – Corcoran Collection] (Wikimedia Commons) |

After twelve or more long hours of walking through crowds of people and being interviewed by numerous immigration agents, Sander was finally finished – he had been admitted to the United States. Because it was well into the evening, an agent from the National Line escorted Sander and others to their lodgings. Within the next day or two, he would board a train for the last leg of his journey.

When it was time to go to the train station, the newly arrived immigrants were escorted to ferries that took them across the Hudson River to the Pennsylvania Railroad Station in Jersey City, New Jersey.

|

|

Courtlandt Street and Liberty Street

Ferries. (Wikimedia Commons)

|

_pg123_PENNSYLVANIA_RAILROAD,_JERSEY-CITY_STATION_wikimedia.jpg) |

|

Pennsylvania

Railroad's Jersey City Station, 1893. (Wikimedia Commons)

|

|

|

Emigrants Embarking at the Railroad Station

in New York for their New Homes in the West. May 1880. (LOC)

|

|

| General map of the Pennsylvania Railroad and its connections. 1893. (LOC) My red dot indicates where Sander ended his journey in Stoneham. [The Stoneham depot was torn down between 1889 & 1893.] |

Finally, the rails led across the mountainous Allegheny Plateau. It was covered with countless high ridges and deep valleys formed by ancient glaciers. Because of the dense forests and his limited view from the train, Sander was sometimes surprised when the train suddenly broke into the open as it traversed a railroad bridge spanning a deep ravine or valley.

This Google relief map shows the ridges and valleys of the Allegheny Plateau, with my added labeling.

Sander's train

crossed many bridges on its way to Stoneham − looking down when it crossed one could be dizzying. But none of the bridges had the impressive dimensions of the Kinzua Bridge. About

twenty-five miles east of Stoneham, the bridge spanned the Kinzua Creek

Valley. When it was completed in 1882, the 2,052-foot-long, 301-foot-high trestle was the longest, tallest railroad bridge in the world, a designation that lasted for two years. From the beginning, trains traversing the Kinzua Bridge were

limited to a speed of five miles per hour because locomotives made the

bridge vibrate. (Wikipedia)

|

| Aerial view of the Kinzua Bridge and Kinzua Creek Valley circa 1968. (LOC) |

|

| The Allegheny National Forest near Warren, Pennsylvania. |

Sander’s 350-mile journey across Pennsylvania could have taken three or four days, although it's difficult to determine since there were many delays as the train stopped at numerous stations to load and unload passengers and their baggage, while taking on wood and coal to replenish the fuel supply. In all, by the time he arrived in Stoneham Sander had traveled nearly 5,000 miles in just under three weeks.

As the train slowly came to a halt at the Stoneham depot,

Sander looked out the window at the forested hills that would surround him in his new life. He felt apprehensive, excited, and incredibly tired. After taking a deep breath, he stepped off the train. And there was Clara—he was home.

|

| A postcard, circa 1909, depicting a train at the Pennsylvania Railroad depot in Warren, four miles from Stoneham. |

|

| L: Clara Marie Palm (1864-1935) R: Clara and her husband, Axel Johnson |

* * *

~ Immigrant’s Voyage in Steerage, 1888 is an abbreviated account of writer Eliza Putnam Heaton's experiences as a steerage passenger on a voyage from Liverpool to New York City for the purpose of documenting conditions encountered by immigrants.

The full account, entitled A Sham Immigrant's Voyage in Steerage – 1888, can be found at GG Archives.

~ Read more about the Elephant Hotel and fascinating history of Coney Island at The Heart of Coney Island.

No comments:

Post a Comment